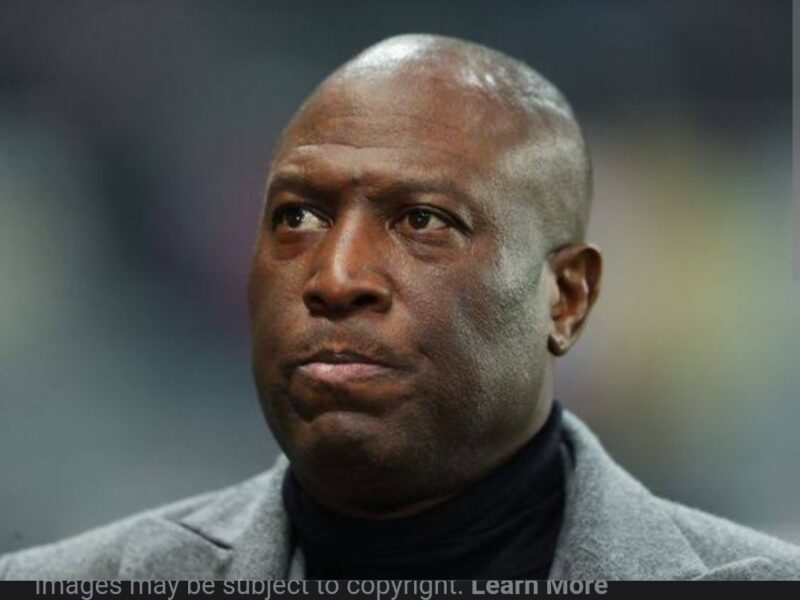

In a special interview for Black History Month, Chris Beesley speaks about Kevin Campbell’s legacy at Everton and Arsenal with Dr Clive Nwonka

Kevin Campbell’s heroics for Everton have been hailed as an amazing football renaissance story and even though the striker often played second fiddle to Ian Wright earlier in his career at Arsenal, an incident when he challenged the club’s owner showed why he would go on to become the Blues’ first black captain. That’s the view of Dr Clive Nwonka, Associate Professor of Film, Culture and Society at University College London, who is co-editor of a new book, .

With terraces being demolished in English top flight football following the Hillsborough disaster, Arsenal decided to hide all the scaffolding, cement trucks and cranes with a large piece of artwork dubbed ‘The Highbury Mural’ as they rebuilt the North Bank. On the day before Arsenal’s inaugural Premier League fixture in August 1992, the first team were taking part in their final training session before the big kick-off at the ground.

As the Gunners’ co-owner and vice chairman David Dein walked along the perimeter of the pitch, a then 22-year-old Campbell stopped him and said: “There are no black faces on this mural.” Dein looked up and replied: “Yes, you’re absolutely right, that’s unacceptable.”

READ MORE: Behind the scenes at Goodison Park captured in amazing images as Everton continue long goodbyeREAD MORE: Everton could make bargain transfer move for ‘late bloomer’ who plays like £32m record-breaker

Overnight worked ensued and by the time Arsenal welcomed Norwich City the next day, the artwork depicted a more accurate reflection of the club’s multicultural fanbase.

Everton In The Community Forever

Everton In The Community Forever

Sign up to FREE email alerts from Everton FC

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and third parties based on our knowledge of you. More info

Speaking in a special interview to mark Black History Month, Dr Nwonka told the ECHO: “In the book I talk about the famous Arsenal North Bank mural in 1992. Kevin was still a relatively young player at the time but for him to have the temerity at that age to see that and recognise that what the North Bank imagery was showing, wasn’t reflective of the fanbase, and then challenge David Dein and say ‘listen, that’s wrong, that isn’t the Arsenal fanbase which is multicultural,’ shows so much about him and it’s no surprise that he became Everton captain, because he unified people.

“Equally, I think a triumph of Kevin Campbell from his Everton days is showing how the understudy – which he was at Arsenal – can eventually come into his own fruition. He was one of those instances in football where a player who was in the shadow of a more-recognised, maybe louder, colleague, has blossomed later on, at the right time.

“When Kevin left Arsenal and went to Nottingham Forest, it seemed like his career was on the slide, so after being kind of forgotten about in Turkey, to have that renaissance and come back and do what he did at Everton is an amazing story. Coming in and scoring nine goals in five games, surely goes down as one of the most-important moments in Everton’s recent history.”

Unlike his experiences at his first club Arsenal, Lambeth-born Campbell, who made his senior debut against the Blues at Goodison Park on May 7, 1988, coming on as a 78th-minute substitute for Martin Hayes, who had earlier netted what proved to be the winner in a 2-1 victory, was joining a club with a very different background when he came to Merseyside. Never mind supporters in the stands, Everton didn’t even have a single black player in their team for the first two Premier League seasons.

However, little over a decade after John Barnes was photographed backheeling a banana that had been thrown at him during a Merseyside Derby at Goodison, Campbell became the Blues’ saviour. Dr Nwonka said: “The club culture and the city will have changed. Kevin, in many ways, will have transcended Goodison Park and throughout the city, that evolution.

“I know that Everton weren’t in a great place when Kevin joined them, but I think it was a great move for him. I remember that there had been other black players at Everton earlier in the 1990s like Daniel Amokachi, Earl Barrett and Danny Cadamarteri, but they hadn’t been around for a particularly long time.

“Kevin became an instant cult hero though, which was kind of unexpected maybe, but he essentially saved Everton from relegation when he came in at the end of his first season. Any one of the different strikers he ended up being paired with were successful too.

“He didn’t just get the captaincy because he was experienced, but rather because he’d become an amazing idol with the fans in a manner that was akin to how he’d been viewed by Arsenal fans. To do that in a city like Liverpool for a team like Everton, who had entered the Premier League era without any black players, in many ways, Kevin became to Everton what John Barnes had been to Liverpool.”

Indeed, despite his publication, Dr Nwonka is not even an Arsenal supporter and he credits Barnes’ influence for ensuring that his own personal allegiances lie across Stanley Park having followed Everton’s neighbours’ fortunes from afar as a youngster. He said: “The idea for the book Black Arsenal came about eight or nine years ago. I was working in the sociology department of the London School of Economics, and I was thinking about things like identity and culture from my own childhood.

“I’m actually a huge Liverpool fan! People think that I’m an Arsenal fan but I actually grew up as a Liverpool fan because of John Barnes.

“As a black person, he was a massive inspiration for me and every other young kid, looking through sticker albums and him being the only black player in there. I remember watching him against Wimbledon in 1988 and Arsenal in 1989 and beyond.

“I was looking back at how important he was in a sense of young, black masculinity for me in London in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By the time I got to about the age of eight, nine or 10, there was a new kind of cultural icon emerging.

“He was also black and male but had more of a, dare I say, working class, respect and attitude, and that was Ian Wright. For Arsenal, there was just something about that particular moment in time in the early 1990s in terms of being black and being British and how it was being contested in different ways.

“In athletics there was Linford Christie and boxing had Frank Bruno while there were other things like music, fashion and culture. When it came to incapsulating all those things and doing the bogle on the pitch and the way he carried himself with a gold tooth, Ian Wright looked like people who were older than me in the barbershop.

“Looking back and thinking why that was important, Arsenal also seemed important in terms of gluing all those things together. I started to piece together different elements and I wasn’t sure what it would be, whether it would end up being a seminar or a podcast, but having done a talk at the Barbican a few years’ later, it sold out in about 24 hours.

“Members of the club came down, there were fans and ex-players, and at that point I realised that things I thought were just simply in my head were resonating with other people. Initially, I thought of writing it as a single author book as an academic thing, as someone who understands Arsenal, appreciates Arsenal but is not an Arsenal fan per se, but then I decided to produce something that was a composite of different perspectives and got Matt Harle, who is an Arsenal fan, involved, and that became Black Arsenal.”

At Arsenal, Campbell was part of a clutch of homegrown black players with the likes of Paul Davis (1980); David Rocastle (1985) and Michael Thomas (1987) all making their first team debuts before him. Dr Nwonka said: “Paul Davis is so central to the book because without him and what he experienced and what he went through, being at the club for 15 years, including the bad times in the 1980s when he’d go to away grounds and being racially abused was commonplace, if he hadn’t been through that, maybe there wouldn’t have been a ‘Rocky’ Rocastle, a Mickey Thomas or a Kevin Campbell. In terms of the book, Kevin was very important for me because my first real encounter with Arsenal was when my older cousin took me to the 1991 League Championship parade around Highbury.

“As the bus came around, I noticed Kevin Campbell hanging out from the top deck and it’s an image that stuck with me. In the book there is a lot of imagery around Kevin and he was always seen as the understudy to Ian Wright, but he was a fantastic player in his own right.

“He was always someone who was spoken about in the barbershop, the churches or the playgrounds in a similar way to Wright. He got me thinking about that connection between the black community in London and Arsenal.”

Campbell’s death at Manchester Royal Infirmary on June 15 this year from multi-organ failure due to a heart infection, left football fans across the country, and in London and Merseyside in particular, devastated. Like this correspondent at the ECHO, who had reached out to Campbell in an attempt to get him in as a guest for the Goodison Park: My Home series, Dr Nwonka was taken aback by the 54-year-old’s rapid decline in health and felt it essential to mark his passing in the book.

He said: “When the book was finished, I said how I really wanted Kevin to be on stage with Ian Wright and Paul Davis as they were three of the pioneers. Then one day I just heard he was really ill.

“When he died, it was a real shocker. One of the first things I did was to contact the publishers and say we needed to stop the printing because we needed to get some kind of tribute on the first page.

“I didn’t care what the cost of the implications might have been, but we needed to do that. Thankfully, the publishers were completely on board and got the tribute in, alongside one for David Rocastle, which was immensely important to both myself, and to the fans.”